Hello everyone! Welcome to another presentation of IN THE WHITE. Hope you all are doing well, as well as in good health.

This is the second part of the “Accessibility: A Right for Persons with Disabilities” report.

If you have not yet read part 1, then I would suggest going through that first for a better understanding of this content.

Hope you will find this interesting and informative.

ACCESS TO INFRASTRUCTURE

The most important component in terms of accessibility for persons with disabilities is infrastructure. Without this element persons with disabilities will not be able to move around freely and independently, especially those in wheelchairs. The report identifies two types of disabilities, namely the visually impaired and the physically challenged who are the most vulnerable to accidents if“reasonable access to all indoor and outdoor places, public transport and reasonable adaptation of buildings, infrastructures” (Rights of Persons with Disabilities Acts 2018, 2018) are not met. Providing a strong infrastructure is not only a government’s duty to be fulfilled, but is a motivation for persons with impairment to live an independent life, which further encourages them to achieve the different individual goals they ought to accomplish. Whether it be going to school, work or shopping via public transport like buses and taxies or interisland travel by boats, ships or aircraft, “persons with disabilities have full rights to access such services on an equal basis with others” (Rights of Persons with Disabilities Acts 2018, 2018).

Althougsectionson 29 (a) and (d) of the rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2018 assures access to indoor and outdoor places, public transport, and buildings, it is worth noting, not all office blocks are disability friendly. A report by the office of the Auditor General of the Republic of Fiji titled “Performance-Audit on the Access for Persons with Disabilities to Public Office and Public Transport” highlights twenty-seven venues in Suva City, Fiji of which some were partially accessible while others were not accessible completely (OAG Performance Audit-on the Access for Persons with Disabilities to Public Offices and Public-Transport, 2020). The report further mentions of “poor footpath conditions and the lack of curb rumps” (OAG Performance Audit-on the Access for Persons with Disabilities to Public Offices and Public-Transport, 2020) makes it impossible for wheelchair users to cross roads independently.

Similarly, access to public transport remains a test for physically impaired individuals in particular as “none of the public service vehicles are user-friendly” (OAG Performance Audit-on the Access for Persons with Disabilities to Public Offices and Public-Transport, 2020). It must be taken into account that section 61 (1) affirms the right to access public transport for persons with disabilities, but “lack of knowledge within relevant institutions and policymakers it has not been well enforced which acknowledged in the audit report cited in this paper.

ACCESS TO INFORMATION

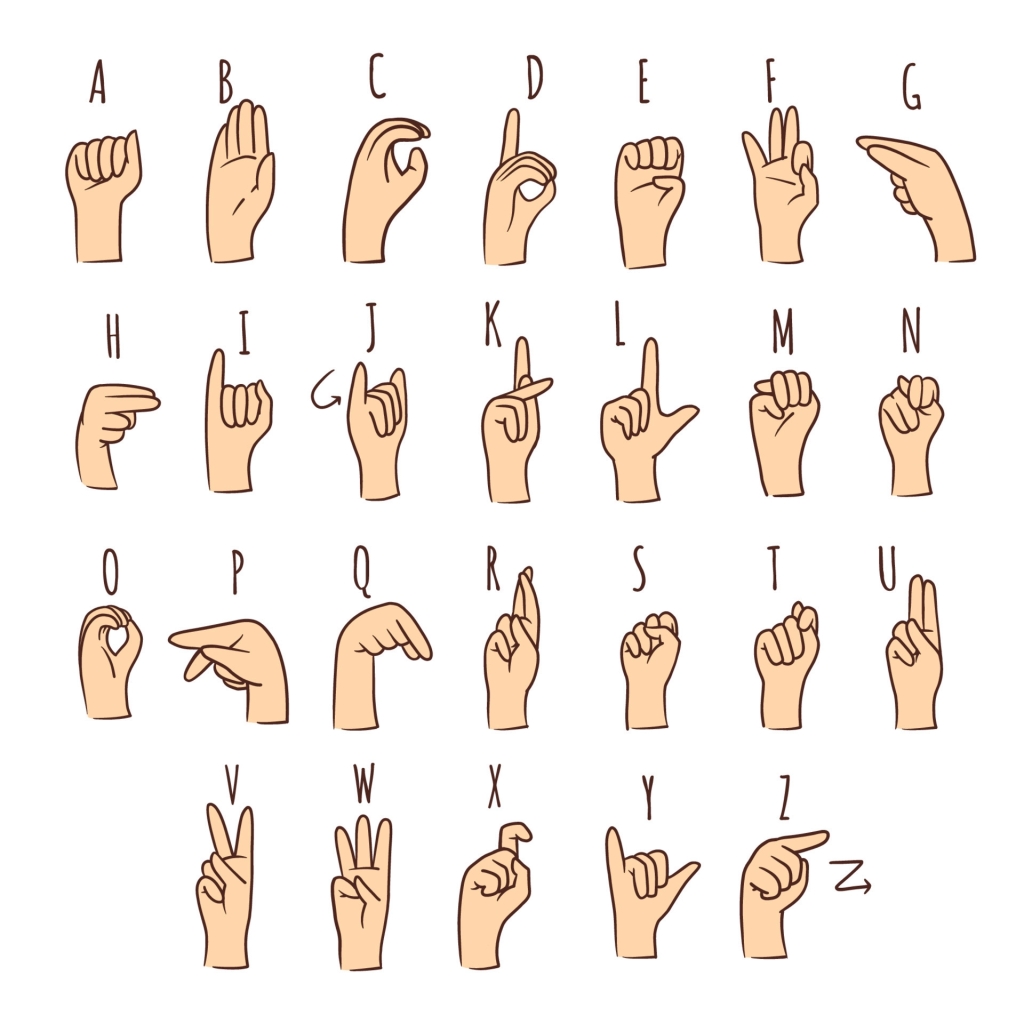

Access to information is a crucial element that Persons with disabilities need to communicate effectively. Disseminating information to the public is an important responsibility for any institution, keeping in mind persons with disabilities are included when any piece of information is shared with the public. When passing a message to persons with impairments, how a piece of information is disseminated must be considered given the different varieties of impairments that exist and the kind of disability or disabilities people are faced with. There are various ways the Fijian government has stated in the Rights of Persons with disabilities act 2018, to ensure individuals with impairments are informed, which include; information through signage, forms in braille as well as in easy to read and understand modes” (Rights of Persons with Disabilities Acts 2018, 2018) must be available in an office block and other facilities open to the public. Pictures, tactile diagrams, and, video clips with the use of sign language interpretation or in cooperation with subtitles are some effective tools that can be useful in getting messages across to persons with disabilities.

Section 25 (1) (a) and (b) of the 2013 Constitution of the Republic of Fiji gives the right of “access to information held by any public officer including another person and required for the exercise or protection of any legal right” (Constitution of the Republic of Fiji, 2013), does not exclude information given to persons with disabilities. This right is further reflected under accessibility in the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2018. Section 29 (a) reaffirms access to information apart from accommodating indoor and outdoor facilities and public transport (Rights of Persons with Disabilities Acts 2018, 2018).

However, one must understand physical access to information is not the only barrier persons with disabilities are up against, accessing information online is equally as challenging as that. Digital access to information can be more difficult for the visually impaired in particular, if “screen reading software’s such as Job Access with Speech (JAWS) or Non-Visual Desktop Access (NVDA)” (Kirsty Williamson, 2001) is not provided to such persons. Those with some vision often or may rely on a “screen magnification program” (Kirsty Williamson, 2001) which enlarges text or images enabling the person to see and read. These instruments alongside “optical character recognition” (Kirsty Williamson, 2001) have been utilized globally including the Pacific region which Fiji is also part of, it has proven effective in improving the lives of the visually impaired and the way information is accessed online.

ACCESS TO EDUCATION

Access to education is essential for both children and adults of Persons with disabilities for a promising future and sustainable livelihood. A checklist (Tara Wood) could play a key role in assuring accessibility needs are met to accommodate education requirements for children and persons with special needs. Services such as ramps to classrooms, interpreters for the deaf, and braille machines for the visually impaired (Tara Wood) are necessary facilities that must be available to make learning disability inclusive. It also provides an opportunity for abled-bodied individuals to mingle and learn from the differently abled children and adults, which would further enhance understanding of the different disabilities that exist within society and help combat “discrimination based on disability” (Rights of Persons with Disabilities Acts 2018, 2018) in the community.

The “Special and Inclusive Education Policy” (Policy on Special and Inclusive Education, 2016) developed by the Education Ministry is a reflection of Fiji’s commitment to the inclusion of children with special needs in the education arena. Section 2.3 of the policy assures “necessary support to schools through adequate staffing, teaching/learning resources, and infrastructure” (Policy on Special and Inclusive Education, 2016) to facilitate children with disabilities.

The barrier in the effort to implement the legislation could be understood in an article titled “Mobilising School and Community Engagement to Implement Disability-Inclusive Education through Action Research: Fiji, Samoa, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu”, which highlights challenges namely the expensiveness of constructing rumps in schools and the conservative mindset of school management that represent community values continue to hinder education inclusivity.